Social media is where people express opinions about many topics, including movies, vacations, meals, and major political events. Of course, scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory are not the first to recognize this. But now researchers at the Lab are using social media platforms—instead of traditional polling—to quickly gauge public sentiment on matters of national and global importance.

“[Social media] was such a rich set of data, and it wasn’t being explored.”

Traditional polling involves an interested party hiring workers to ask peoples’ opinions about a particular issue. But this can be expensive. It can also take a lot of time to write objective questions, to prep a team for interviews, and, for in-person polling, to have pollers knock on doors.

In some countries, pollers could have difficulty or face danger when trying to reach some parts of the population, such as people living in the jungles of Colombia. Since the 1960s, remote regions of Colombia have been controlled by dangerous Marxist rebel groups, including the large and powerful Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). During its 50-plus-year existence, FARC has kidnapped and killed thousands of people. Even so, in the years leading up to the 2016 peace deal between FARC and Colombia, the country’s citizens had mixed reactions.

“During peace negotiations, people from all over Colombia were on social media, posting publicly about how they felt,” says Ashlynn Daughton, an information scientist at the Lab. “It was such a rich set of data, and it wasn’t being explored. And from the past we know it’s absolutely necessary that the public support these kinds of talks, or they’ll eventually fail.”

In 2020, Daughton decided to see if public sentiment could be polled via social media. Her team created a timeline of pivotal events during the Colombia peace-deal talks. Daughton then overlaid that timeline with 720,915 tweets, posted publicly between 2010 and 2018, by Twitter users in Colombia. To weed out irrelevant tweets, her team used unsupervised machine learning to group hashtags and peace talk–related Spanish words, such as the names of politicians or groups involved in the peace talks, and other words commonly associated with the negotiations. Daughton’s team then analyzed each tweet using Stanford University’s CoreNLP language-analyzing software.

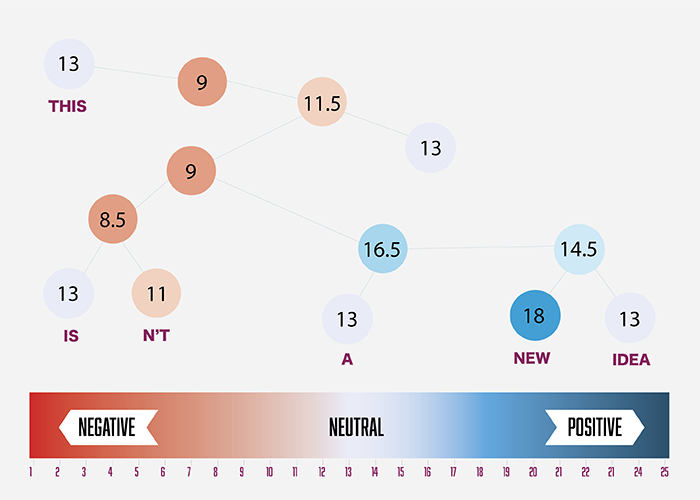

CoreNLP dissects a sentence and creates a “sentiment tree branch” that assigns each word and group of words a score from “very positive” to “very negative.” The entire sentence is then assigned a value. With this new system, Daughton found that she could gauge the country’s sentiment toward the peace talks immediately following important events during the negotiation process—such as the shooting of 11 government soldiers in 2015, a major setback to the peace talks.

When compared with polls at the time, Daughton’s method was just as accurate (although it’s important to note that polling data is rare, so Daughton’s findings cannot be fully validated). And although this study re-created past events, it proved that, going forward, social media provides a valuable data set that, when combined with traditional polling data, may help future governments reach peace deals more quickly with more calculated steps.